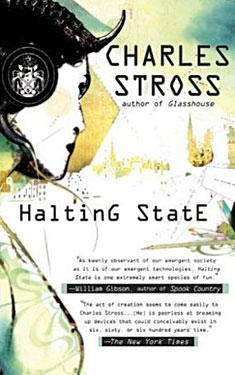

Charles Stross

Completed 7/13/2015, Reviewed 7/15/2015

2 stars

Steve (You think you’re being so smart)

The first thing that hits you about “Halting State” is that

it is writing in second person present.

This means that you are the character.

And just like this review, you’re the narrator. You think this might be fun, a form you’ve

never experienced before, except in math problems where you have two apples and

someone gives you two more… But your

interest in the form fades as you discover that the narration alternates

between three character and what passes as prose leaves you confused and angry

through most of the book.

Your gist of the plot is that it reminds you of standard

non-genre best seller intrigue. In the

near future, a virtual robbery takes place in a game owned and operated by

Hayek Associates. They call the

cops. Officer Sue is the first to

arrive, trying to wrap her head around the need for local police involvement in

a virtual crime. Hayek’s insurance

company sends Elaine, an auditor/game player and Jack, a power game

developer/player to determine if there is fraud to avoid paying the insurance

money. During these three characters’

investigations, they expose an international plot linked to espionage and

terrorism. You guess what makes this

book genre is that it takes place in the near future where there are video

cameras everywhere, cars and taxis are driverless, and google vision is

ubiquitous.

Your gist of the plot is that it reminds you of standard

non-genre best seller intrigue. In the

near future, a virtual robbery takes place in a game owned and operated by

Hayek Associates. They call the

cops. Officer Sue is the first to

arrive, trying to wrap her head around the need for local police involvement in

a virtual crime. Hayek’s insurance

company sends Elaine, an auditor/game player and Jack, a power game

developer/player to determine if there is fraud to avoid paying the insurance

money. During these three characters’

investigations, they expose an international plot linked to espionage and

terrorism. You guess what makes this

book genre is that it takes place in the near future where there are video

cameras everywhere, cars and taxis are driverless, and google vision is

ubiquitous.

Your problems begin in the first chapter. Officer Sue is the narrator. She thinks in future cop jargon. And she thinks a lot. What passes for prose in this book is that

the narrator begins speaking, pauses for a paragraph of jargon thought, then

finishes speaking. This makes most of

the text feel like an aside. It’s

supposed to help carry the mystery of who’s behind the bank robbery and what

the real implications are. Instead, it

makes every paragraph heavy and complicated.

In the second chapter, Elaine the auditor is the

narrator. Now you have to switch

perspective, trying to separate your experience as Elaine from Sue. She comes with a new set of jargon and

thought processes. Finally, Jack the

developer is the narrator. He thinks in

game and programming jargon. Juggling

these three points of view is exhausting.

Despite the chapter headings indicating who you are, it takes you a few

pages to completely switch your perspective, making you reread sections

multiple times to make sure you correctly understand who you are and what you just

read.

About halfway through the book, you’re over it. You force yourself to get to the big

reveal. The complexities of the plot and

are lost on you because of the form. It

reminds you of Chabon’s “Yiddish Policeman’s Union”, where the prose was

distracting rather than helpful in the world and character building. You also believe that not being a gamer is a

big hindrance in your understanding of what’s going on a lot of the time. In contrast, you love Cline’s “Ready Player

One”, which was about arcade games from the ‘80s, where your gaming experience

began and ended.

You really wanted to give this book one star out of five,

because your experience with it was so terrible. You think you’ll never read anything in

second person present again. But you

give it two, because you appreciate the author’s ability to carry the plot

through three very different perspectives, even though it was lost on you.

No comments:

Post a Comment