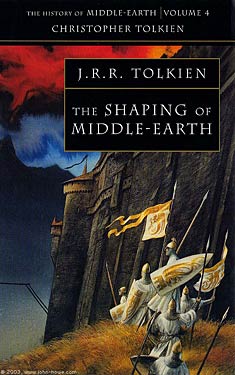

JRR Tolkien

Completed 4/21/2016, reviewed 4/21/2016

4 stars

This is the fourth book in the History of Middle Earth

series. This book gives us the early

development of Tolkien’s thoughts on The Silmarillion. At this point in time, Tolkien was moving

away from the framework he used in The Lost Tales. It still contains the same mythology but is

being constructed and rewritten differently.

Once again, I followed along with The Tolkien Professor’s analysis to

help me understand the text and commentary.

As I progress through the series, the stories are becoming very

familiar. It’s the commentary that’s

much drier. Christopher Tolkien spends

most of his time detailing the evolution of the names as well as pointing out

the detailed differences between all the versions of the stories from The Lost

Tales up to the ‘30s, when much of this text was written. I still find all this fascinating even though

it is often dry as dust.

The book begins with some fragments from the Lost Tales, but

moves into full swing with Tolkien’s first outline of the Silmarillion,

referred to as the Sketch. This is

followed by an initial fleshing out of the outline, called Quenta. The Quenta is basically the first prose

version of the Silmarillion that Tolkien ever produced. It has most of the stories from Lost Tales,

though they have evolved by about 10 to 20 years. The prose is often delicious. Now that I am

as familiar as I am with these stories going through the History, I’m finding

myself really paying attention to the prose to see how he retells these

immensely tragic stories.

The book begins with some fragments from the Lost Tales, but

moves into full swing with Tolkien’s first outline of the Silmarillion,

referred to as the Sketch. This is

followed by an initial fleshing out of the outline, called Quenta. The Quenta is basically the first prose

version of the Silmarillion that Tolkien ever produced. It has most of the stories from Lost Tales,

though they have evolved by about 10 to 20 years. The prose is often delicious. Now that I am

as familiar as I am with these stories going through the History, I’m finding

myself really paying attention to the prose to see how he retells these

immensely tragic stories.

The next two chapters are related. The first shows maps of the construction and

evolution of Middle Earth, the second is the Ambarkanta, the prose

cosmology. Tolkien discusses the makeup

of the atmosphere and the shape Middle Earth, beginning as a flat, uniform

earth and eventually becoming round and turning into continents looking vaguely

like Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The final chapters are annals of the Silmarillion. They are breakdowns of the stories of the

Silmarillion by year. There are two sets

of annals. It’s interesting that one of

them, the Annals of Bereliand, reads like you’d expect, terse outlines by year

of events. The other, the Annals of

Valinor, is almost like another go at a prose version of the stories. It is quite readable. Included in these chapters are Anglo-Saxon

versions of the annals. Needless to say,

don’t understand Anglo-Saxon, but it shows that Tolkien still had the idea that

the point of his stories was to create a mythology for England.

As I always say, this book is for the hard-core fan that

wants to see how Tolkien’s stories evolved over the years. You have to be quite the fan to read for a

fifth time the tragic tales of Turin Turambar or Beren and Luthien. But I find it interesting to see how the

stories changed and grew over the years and look forward to rereading the

Silmarillion again at some point with all this additional background swimming

around in my head. I give this book four

out of five stars.

No comments:

Post a Comment