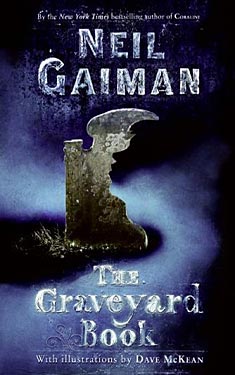

Neil Gaiman

Completed 3/2013, reviewed 5/24/2013

5 stars

The Graveyard Book is a wonderful horror novel for young

teens. The story follows the young life

of an infant whose parents are murdered. He is found, reared, and protected by the

ghosts of a graveyard. At various times

in my reading of it, I thought the premise of the book was too dark for the

targeted age group. But not being a

parent, I eventually gave up my concerns and just enjoyed a great story.

The ghosts in the graveyard are wonderfully endearing. They work together to protect and raise

Bod. They are an eclectic group from

different eras, different classes, and different temperaments. They are a joy to meet. I wished the book was longer so we could

spend more time with the ghosts and get more development of their stories.

The ghosts in the graveyard are wonderfully endearing. They work together to protect and raise

Bod. They are an eclectic group from

different eras, different classes, and different temperaments. They are a joy to meet. I wished the book was longer so we could

spend more time with the ghosts and get more development of their stories.

I have to say I loved every chapter of the book. I want to particularly mention the Danse

Macabre. It is an incredibly bizarre and

engrossing sequence. It reminded me of

some of the bizarre scenes from Clive Barker.

Now that I am writing about it, I don’t quite know what to say about

it. I think I just loved the bizarreness

of it, how the living and the dead can be bewitched into a dancing frenzy, and

afterwards not be remembered by living, or spoken of by the dead.

I loved Bod’s attempts to become integrated with the living,

walking through town, going to school, and meeting a girl. Yeah, it’s kind of the typical disaffected

teenager story, but I really enjoyed it.

It’s been a while since I read the book, so I don’t have

that many specifics anymore. What comes

to me when I reminisce about the book is the warm feeling I had while reading

it. It is easily a 4 star book, with

great characterization and imaginative scenarios.

Postscript 3/1/2016:

A few months after writing this review, I had the opportunity to listen

to the book on CD read by Gaiman. When

we got to the end, I had tears rolling down my eyes. I had to be careful though because I was driving

back from Alaska, and simply breaking down wasn’t an option. Because of this I elevated the rating from 4

stars to 5. Now when I think back on the

book, I just don’t get a warm feeling inside, I get a very powerful emotional

response.