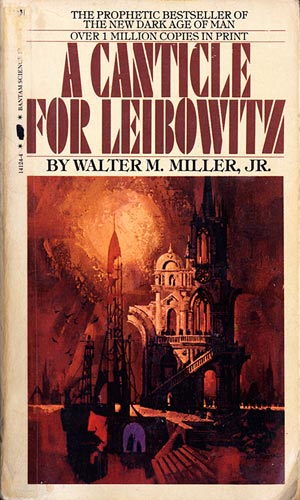

Walter M Miller, Jr

Read in fall semester 1981, late 2012, and completed again

on 12/18/2013, reviewed 12/18/2013

5 stars

How do you review a book you love so much that you read it

multiple times and after each reading, hold it in complete awe? Canticle for Leibowitz is that book for

me. I find so many themes, ideas, and

questions in it that I don’t know where to begin my review. So I’m just going to start writing and see if

I can communicate the profound effect this book has on me.

“Canticle” was originally written as three distinct short

stories. When Miller converted the

stories into a novel, he made heavy revisions to create continuity while

keeping each story distinct. The first

story is set in the post-apocalyptic dark ages of the 26th century. Somewhere in the American Southwest, Brother

Francis, a novice monk at the Albertian Order of Leibowitz abbey, finds what

might be relics of Isaac Edward Leibowitz and his wife. Leibowitz was an engineer who, after a great

nuclear war, and coming to the conclusion that his wife was a casualty of the

war, converts to Catholicism and starts a monastic order whose mission is to

save books which are being purged by the angry rabble left in the war’s

wake. Leibowitz is discovered and

martyred as one of the intellectual elite who contributed to the buildup of

technology that caused the war. The

relics may lead to the canonization of Leibowitz. The story details Brother Francis struggle as

the discoverer of the relics and receiver of a possible vision of Leibowitz

himself.

The second section is set 600 years later. The abbey is at the center of controvery over

its guarding of the ancient memorabilia of the 20th century. Thon Taddeo, a brilliant scientist from a

nearby kingdom, goes to the abbey to inspect the documents himself, discovering

that the monks themselves have discovered how to generate electricity and

create a light bulb based on the memorabilia and Thon Taddeo’s work. The world appears to be at the dawn of new Renaissance. But like the Renaissance of the 15th

century, there is fighting between the kingdoms, conflict over the new

discoveries, and a potential schism in the Church, not unlike that Henry VIII’s

formation of the Church of England.

The third section takes us another 600 years into the

future. Now the abbey is coping with a

world on the brink of another nuclear holocaust. The current abbot, Dom Zerchi, has the task

of selecting some of his monks to leave the earth in the event the war comes to

fruition, taking the holy ancient memorabilia with them and keeping the Church

alive on one of earth’s colonies. Zerchi

must also deal with the question of euthanasia for severe victims of radiation

poisoning, and whether the second head of woman with a genetic mutation has its

own soul.

The three stories create a future history of the earth,

covering a second dark ages, renaissance, and nuclear age, mimicking our own

history after the fall of the Rome .

Once again, the Church saves science,

although this time, it’s not Plato and Aristotle, and Euclid ,

but Newton ,

Einstein, and Leibowitz. No one may

still be able to understand the past, but the Church works to preserve it. What’s different this time, at least

according to the novel, is that the Church isn’t burning what may be

heretical. It’s the common people who

are burning books, all books.

When I first read this book, I found it to be a criticism of

Christianity. Now I’m not so sure. As another reviewer noted, it’s hard to tell

if this is a critique of or a love letter to the Church. For example, I initially thought the

suffering of Brother Francis and the road to Leibowitz’s canonization was a

statement about Church hagiography. Now

it feels more like an homage to stories like St Bernadette of Lourdes and the early missionary

martyrs. If you’ve seen the old film

“Song of Bernadette” with Jennifer Jones and Vincent Price, might get the Lourdes analogy.

Another good example of my quandary is Dom Zerchi’s fight

over euthanasia. I can’t tell what side

of the issue Miller was on. In fact, the

whole third section initially felt like he’s criticizing the theology of

pre-Vatican II Rome. But on my third

read, I felt more like he was siding with the Church. It seemed more like he was really speaking to

the Church’s lack of moral authority in the secular present. Yet, if Miller was siding with the Church’s

stance on euthanasia, then the more ironic is Miller’s own death from

suicide.

Probably the most confusing point is his description of New

Rome. It is full of all the splendor and

vulgarity of our Rome . But upon closer inspection, the plaster is

cracked and falling, the paintings are faded, and the pope’s vestments are worn

and moth-eaten. Again, at first I

thought he was describing the façade of Rome

in the late ‘50’s. It looks wondrous,

but is it really just lipstick on a pig.

And is the pope just a nice, old, friendly guy, or is he just a

doddering fool oblivious to the hardship of life on the plains?

I don’t have answers to any of my questions. I just know it makes me want to read it again

and again, and maybe even do some real research on Miller… I mean, besides

Wikipedia.

Miller’s characterization is very strong. I found that I could fully experience the

viewpoints of all the main characters.

Brother Francis is my favorite character, maybe one of my favorite

characters in all of SF. He grows from

being a terrified novice to a deeply spiritual monk. His journey is at times comical, but is more

often poignant and incredibly touching. His

innocence and reverence serve as a stark contrast to Abbot Arkos’ fear and

cynicism. As much as I love the whole

book, I could read a whole novel just of him.

The hermit is an awesome character. I love the question of whether or not he is

Lazarus, as well as the mystery of a resurrected being. If Lazarus was raised from the dead, then

shouldn’t he be immortal, and what is the implication? Here, he gets to be a comical character,

offering interesting perspectives, often like a Greek chorus.

I do not want to dissuade potential readers from discovering

the magic of this book because of my quandary over what Miller’s message might

be. It is a brilliant book. As I have read through all the Hugo winners,

my experience with this book was the standard against which I held all the

others. This is what a 5 star book

should be.

I didn't initially rate this super high but it has stuck with me over time in a way that none of the other early hugo winners have. Really great, and I can't wait to reread it myself.

ReplyDeleteAnd this is a good one for a reread, as it is relatively short, and still has the feel of being three short stories.

Delete